2 The Impact of Generative Artificial Intelligence on the Existing Intellectual Property Legal System

Generative Artificial Intelligence is first involved in the fields of image, music, film, text and other artistic creations, etc. AI can process large-scale data and generate a large amount of content in a very short period of time compared to human creators, who may take a much longer period of time to accomplish similar tasks. This efficient creation speed can accelerate the output and distribution cycle of content. In addition AI can automate most of the creation process, thus reducing the cost of content creation, while learning and drawing inspiration from massive amounts of data to generate creative and novel content, exploring different styles, themes, and structures, and providing creators with new ideas and inspirations.AI can also automatically customize content according to users' needs, and produce personalized works. This convenience has allowed generative AI to rapidly gain traction in the content creation industry, but it has also had a significant impact on the centuries-old intellectual property legal system.

▲ Figure source network

2.1 Copyrightability of AI-Generated Works

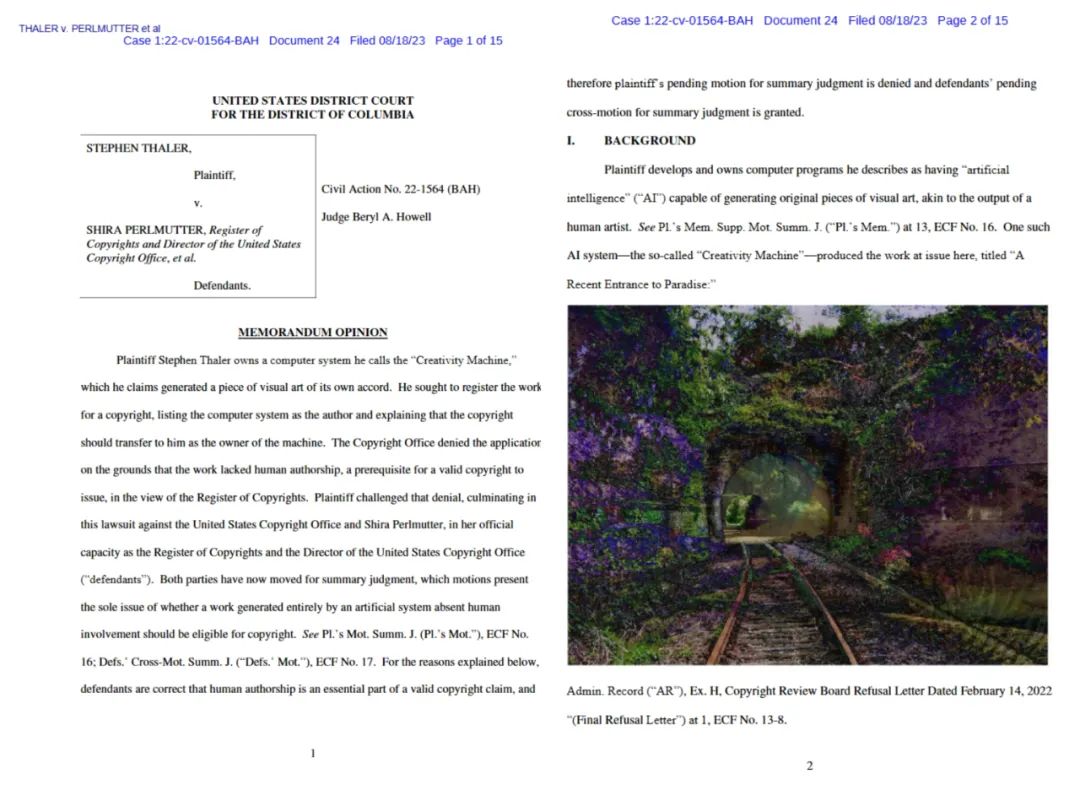

STEPHEN THALER v. SHIRA PERLMUTTER

Since the artworks generated by generative AI products are sampled from the existing data in the large model and automatically generated by AI, it is difficult to determine whether such generative works have the “originality” as stipulated in Article 3 of the Copyright Law, and whether they can be categorized as “intellectual achievements” of human beings. and whether they can be categorized as “intellectual achievements” of human beings. From the judicial practice of major economies in China, the United States and Europe, there are relevant judgments that support the copyright of such works, such as China's (2019) Yue 0305 Minchu 14004 judgment court recognized the use of AI software to write financial news reports of copyrightability; at the same time, there are also jurisprudence that does not recognize the copyright of AI-generated works, such as the U.S. District Judge Beryl A. Howell in STEPHEN THERESIS, the court of appeals in the case of the United States, the court of appeal in the case of the United States District Court of the United States of America. Howell in STEPHEN THALER v. SHIRA PERLMUTTER. Summarizing these jurisprudence, it is not difficult to find that for whether AI-generated works are copyrightable, the focus is on whether the works contain human creative elements.

In the judgments that do not recognize AI works as copyrightable, it is generally accepted that works generated by automatic operation are created entirely by machines or purely mechanical processes, without any creative input or intervention from human authors, and therefore do not have human intellectual output. In contrast, a work can only be protected by copyright law if it contains elements of human creativity. Of course, for more complex cases, such as secondary screening of generated content using nested AI software, the degree of human involvement in generating the work needs to be further assessed. Therefore, the criteria for determining the extent of human participation in creation that constitutes a copyrightable work still needs to be explored and guidelines developed in future judicial practice.

2.2 Attribution of Copyright Rights in AI-Generated Works

Generative AI-generated works have the participation of data sources, model developers and product users, so if the AI-generated work meets the criteria of human intellectual input mentioned above, to whom should the copyright of the work belong?

The law does not make clear provisions on this issue.

Generative AI product providers will generally agree on the attribution of AI-generated content through user agreements, for example, OpenAI clearly stipulates in its user agreement: “OpenAI transfers all rights and interests in the output content to the user, and OpenAI may use the content based on the provision and maintenance of services.Given the nature of machine learning, similar questions may result in identical responses.Requests and generated responses from other users are not considered unique user content.” OpenAI's strategy is to cede the rights to the generated content, while at the same time allowing itself to avoid intellectual property disputes over possible rights flaws in the AI-generated content itself.

Of course, in order to protect the interests of developers, even if it is agreed that the rights and interests in the AI-generated content are vested in the user, certain big model products, such as Notion AI, may require authorization from the user from the user agreement in order to perform operations such as displaying, storing, distributing, reproducing, using, and modifying the derivatives that the user creates through the AI product, so as to enable the application developer to use the user's content for purposes such as monetization, promotion and software upgrades. There are also other software developers who choose to retain the copyright of the AI-generated works and license commercial use only to paying users, among other models, or directly contribute the works to the global public domain through Creative Commons licensing agreements (e.g., the CC0 1.0 agreement) so that others are free to use, modify, distribute, and exploit the works, or even commercialize them, without obtaining the copyright owner's priorwithout the prior permission of the copyright owner.

For AI-generated works where there is no clear agreement on rights attribution or where rights attribution is disputed, the attribution of intellectual property rights is often confirmed through judicial decisions, which often have different outcomes. In one case, the court held that after the plaintiff obtained the authorization of the generative AI software, multiple people from its team collaborated and cooperated with each other in their respective roles, and cooperated with the plaintiff's main creators to use the software to complete the relevant textual works, and therefore, even if the text used the AI generation tool, the user still enjoys the copyright of the textual works; on the contrary, the court held in some cases that the AI-generated content did not convey the software developer'sthoughts and feelings of the software developer, and the software user only automatically generates the content in the form of search, and there is no original expression of the thoughts and feelings of the user given to the content itself, so neither the developer of the large model software nor the user of the product enjoys copyright in the AI-generated content. It can be seen that, as with the copyrightability of AI-generated works, the attribution of copyright in such works is often determined in judicial practice by reference to the extent to which the relevant participants have invested their human intellectual activity in the work and have contributed to the originality of the generated work.

2.3 Copyright infringement risk of AI-generated works

Since generative AI big model products must use existing work data for model training and generate AI-generated content based on the algorithmic model formed by the training work, AI-generated content naturally and inevitably carries memories or traces of the training data, and AI-generated content may present some elements, features and styles of the training work. It is generally recognized that if the content provided by the AI is substantially similar in expression to the training work and there is a possibility of interaction, there may be a legal risk of copyright infringement, which, depending on the circumstances, may constitute an infringement of the right of reproduction, the right of dissemination through information networks or the right of adaptation.

If the AI-generated work constitutes intellectual property infringement, according to the general Civil Code, the user of the infringing work, as the party at fault, bears the main responsibility for the intellectual property infringement, while according to the general principle of the assumption of responsibility of network service providers, i.e., service providers are not required to bear the responsibility for the infringing behaviors of the users who utilize the network service, but should take timely measures to avoid the expansion of damages in the event that the service providers know or should have known of the infringing behaviors of the users.necessary measures to avoid the expansion of damage.

If a generative AI service provider is defined as a network service provider in the general sense, the premise of its liability for infringement is that it “knew or should have known” that the infringement existed.However, according to Article 9 of the Interim Measures, the generative AI service provider shall bear the responsibility equivalent to that of a “content producer”, and actively fulfill its network security obligations. Of course, in order to protect the interests of developers, even if it is agreed that the rights and interests in the AI-generated content are vested in the user, certain big model products, such as Notion AI, may require authorization from the user from the user agreement in order to perform operations such as displaying, storing, distributing, reproducing, using, and modifying the derivatives that the user creates through the AI product, so as to enable the application developer to use the user's content forpurposes such as monetization, promotion and software upgrades.

There are also other software developers who choose to retain the copyright of the AI-generated works and license commercial use only to paying users, among other models, or directly contribute the works to the global public domain through Creative Commons licensing agreements (e.g., the CC0 1.0 agreement) so that others are free to use, modify, distribute, and exploit the works, or even commercialize them, without obtaining the copyright owner's prior

without the prior permission of the copyright owner. For AI-generated works where there is no clear agreement on rights attribution or where rights attribution is disputed, the attribution of intellectual property rights is often confirmed through judicial decisions, which often have different outcomes.

In one case, the court held that after the plaintiff obtained the authorization of the generative AI software, multiple people from its team collaborated and cooperated with each other in their respective roles, and cooperated with the plaintiff's main creators to use the software to complete the relevant textual works, and therefore, even if the text used the AI generation tool, the user still enjoys the copyright of the textual works; on the contrary, the court held in some cases that the AI-generated content did not convey the software developer's

thoughts and feelings of the software developer, and the software user only automatically generates the content in the form of search, and there is no original expression of the thoughts and feelings of the user given to the content itself, so neither the developer of the large model software nor the user of the product enjoys copyright in the AI-generated content.It can be seen that, as with the copyrightability of AI-generated works, the attribution of copyright in such works is often determined in judicial practice by reference to the extent to which the relevant participants have invested their human intellectual activity in the work and have contributed to the originality of the generated work.[...]

Judging from the tendency of previous EU legislation, this bill is in line with the EU's consistent style of strong regulation of the Internet industry, i.e., to restrict the uncontrolled expansion of foreign Internet giants such as Google and ChatGPT in the EU market through legislation, and to emphasize the protection of personal freedom and individual rights.

Of course, the EU's legislative tendency in this area is mainly due to the fact that its development as a whole economy in the Internet era is significantly lagging behind that of the United States and China, so its legislative and law enforcement style of strong regulation of the data network industry can maximize the protection of the EU's single market from the disorderly expansion and monopoly of the Internet giants from outside the region, thus increasing the EU's single market in the global economy and political discourse power in the global economy and politics.In contrast, the UK and US regulatory style for this market is slightly different from that of the EU. The Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights issued by the US in 2022 and 2023, the National Strategic Plan for Artificial Intelligence Research and Development, and the Biden administration's first executive order issued in October 2023 all emphasize the scientific and flexible nature of regulation, with the aim of clearing the barriers to the application of AI technology and promoting technological innovation. The aim is to clear the obstacles to the application of AI technology and promote technological innovation, insisting that the premise of regulation is to encourage the innovation and development of AI, and in terms of specific regulatory details, focusing on preventing the use of AI to design threats such as biological or nuclear weapons, as well as emphasizing cybersecurity for extraterritorial data exchange, while on the contrary, not placing special emphasis on the protection of individual freedoms and rights.

The UK's AI-related regulation, on the other hand, is very much in the traditional British style of industry autonomy. The UK government released the AI White Paper in March 2023, which advocates the formation of non-legislative mandatory industry autonomy standards through industry autonomy, and finally the transformation of industry standards into legislation depending on the state of development of the industry, but at present there is no unanimous agreement on the industry guidelines in the UK, so the UK's legislation in the field of AI will be pushed forward at a relatively slow pace.Through the above attitudes of several mainstream economies to AI regulatory legislation, it is not difficult to see that for the development of AI technology and digital economy is relatively backward economy, its legislative concept is mainly through strong regulation to reduce the impact of AI technology on the local market, so take the path of regulation and then development.Although AI service providers influence the content output of the products through model training and parameter adjustment, for users using the software and subjectively modifying the generated content, AI service providers can not effectively control the content, therefore, the semantics of the Interim Measures may make generative AI product providers in the process of infringement of the works defined as direct content producers rather than network service providers, which undoubtedly creates a huge commercial risk for the service providers of such products.

Therefore, the liability of big model service providers in the infringement of AI-generated works still needs to be further explored in legislation and judicial practice. JAVY3's exploration of regulation of the generative AI industry At the 7th Woodpecker Data Governance Forum, the Generative AI Development and Governance Observation Report (2023) released by the Nandu Digital Economy Governance Research Center highlights the heightened concern of the whole society about the ethical governance of AI.

The report pointed out a series of issues such as false information, algorithmic discrimination, infringement of intellectual property rights, data security, leakage of personal privacy, and employment impacts, which have triggered even stronger concerns about the ethical governance of AI.

▲ Figure source network In response to these issues, countries are actively addressing the impact of the AI industry on society through legislative means, but the regulatory focus of major mainstream economies is slightly different.

The European Union, a pioneer in data and AI-specific legislation, has recently finalized the legislative process for the Artificial Intelligence Act.Based on the core concept of “risk classification,” the bill requires companies that generate AI to disclose any legally protected information and data used to develop their systems.Judging from the tendency of previous EU legislation, this bill is in line with the EU's consistent style of strong regulation of the Internet industry, i.e., to restrict the uncontrolled expansion of foreign Internet giants such as Google and ChatGPT in the EU market through legislation, and to emphasize the protection of personal freedom and individual rights.

© Beijing JAVY Law Firm Beijing ICP Registration No. 18018264-1